Our new movement ecology paper out in the journal Movement Ecology, exploring decision-making across different life stages in food caching Persian leopards in mountains of Iran.

Tackling behavioural questions requires identifying points in space and time where animals make decisions and linking these to environmental variables This is extremely difficult in rugged mountains, species are rare, difficult to see in the wild, and more difficult to follow.

We used hidden Markov models to investigate the ontogeny of behavioural states based on GPS telemetry data, supplemented with field investigation of ca. 310 locations to understand what the leopard were up to, i.e. feeding or resting?

Leopards are known as food caching predators, defined as storing and/or securing food, is an evolutionary strategy adopted by predators which can reduce kleptoparasitism or safeguard surplus food for future consumption.

We found that leopards also do cache food in mountains, but in the absence of tigers/lions/wolves, why they do so? . The answer should be the high density of leopards (ca. 6 individuals/100 km2), making leopards cache their food to avoid being stolen by con-specifics.

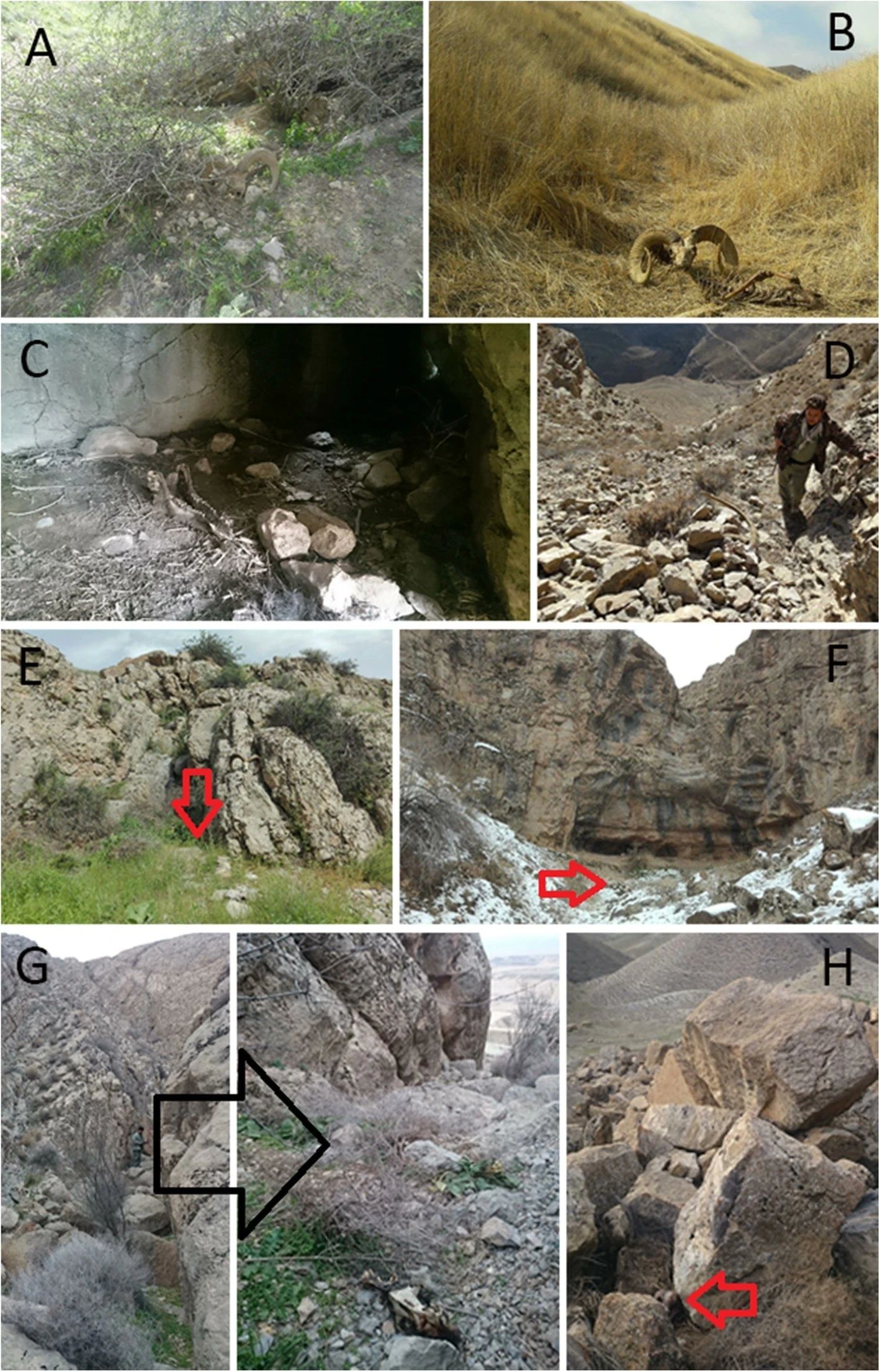

Caching is mostly known from savannas and forests, where leopards cache their food up in the trees, but how they do that in mountains? . In mountains, leopards’ caching strategy is a combination of (see these photos):

A: hoarding the kill within available microhabitat features

B: strictly constrained movements around the kill (mean 52 hours spent within 200 m of each caching site) . Life stage (if a leopard is resident or non-resident) affects movement patterns. How?

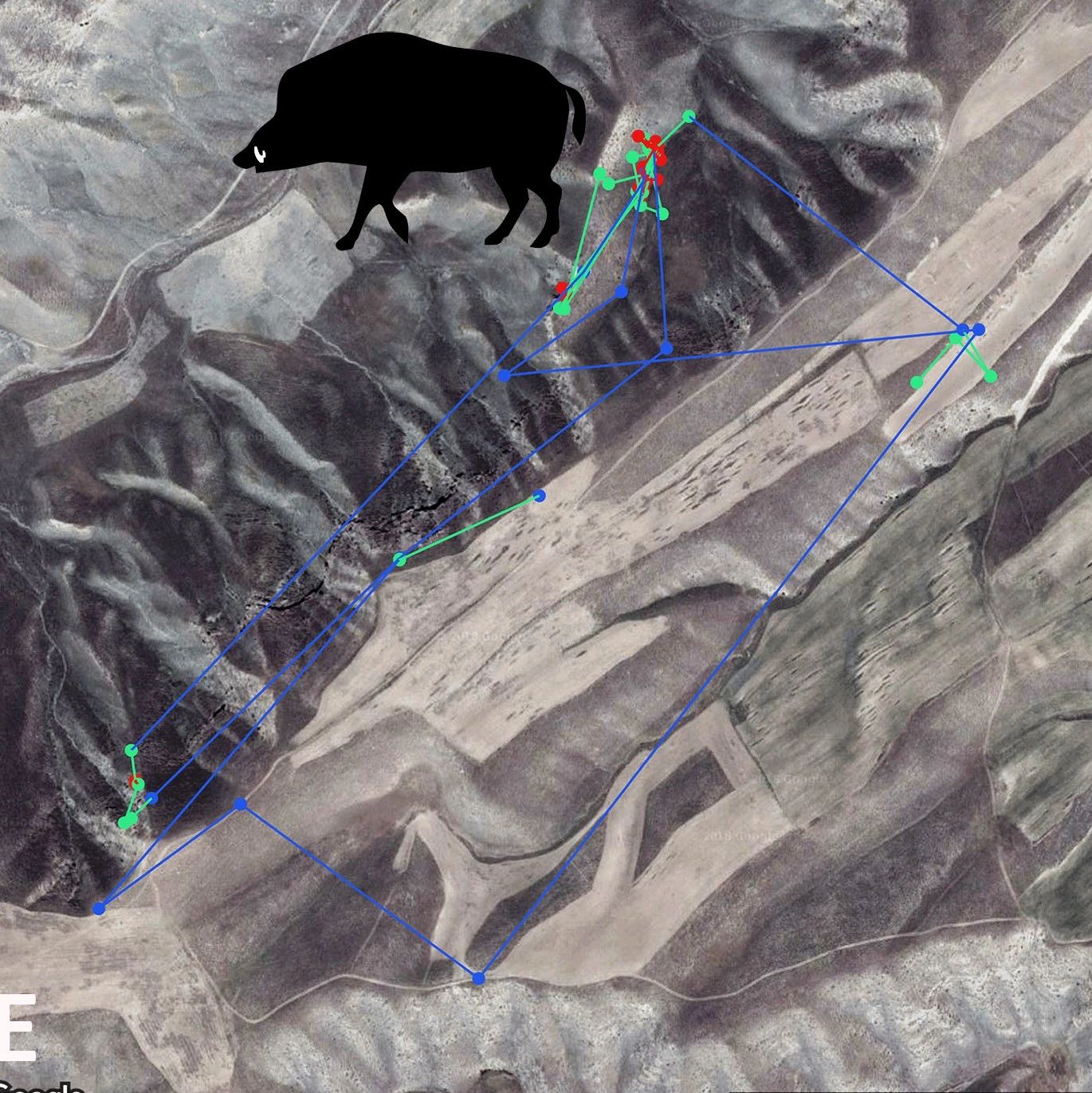

As resident (established home range), leopards are more often in traveling mode with fast directed movement, regardless of hunger level (time since last kill). vs. Nonresidents spend most of their time in less mobile mode (slow undirected movement) Why do they differ?

Residents need to maintain home range regardless of food/thermoregulatory needs, forcing them to adopt energetically costly mobile behaviour. Non-residents need to ensure their foraging needs are met while avoiding conspecifics. So, they adopt less mobile strategy to minimize risk.

In other words, as non-resident, if you are full, rest and do not spare your energy because you do not have any land to protect But if you own a land (resident), no matter how full are you, you must patrol the home range to ensure that it is still owned by you, not your enemies.

Life stage even affects the temporal budget of caching strategy of leopards in mountains. Although both residents and non-residents cache their food, but their movement differs. How?

During caching phase, nonresidents are less mobile than residents, why? Residents have to save their food + land, but nonresidents have no land yet, so they stick to their food Poor resident leopards, how much energy they have to spend for land tenure in high density areas.

We found the hidden Markov models extremely helpful to reconstruct behavioural patterns of such an elusive predator. This cool paper was possible thanks to our extremely helpful field assistants, climbing these beautiful mountains for ca.90 days.

You can see the paper here: